Book Review: Reading Zimbabwe with ‘Nervous Conditions’

Nervous Conditions may have been written in the 80s and set in the 60s but its contemporary relevance to African literature cannot be disputed. It’s one of the most relatable stories I’ve encountered while Reading Africa and a wonderful book to read from Zimbabwe. Following the main character’s transition from village to mission station to private school, Nervous Conditions addresses themes at the intersection of race, gender and class. With powerful characters and intense relationships at its heart, it is the story of how systemic violence reaches into families and, at the most intimate level, into a person’s psyche.

I was not sorry when my brother died. So begins the tale narrated by protagonist Tambudzai. The opening line is revealing. She does not grieve his death, primarily because it provides an opportunity that she would not otherwise have had — the opportunity of a ‘superior’ education and life in a westernised household. In the book, the first of a trilogy, we see how Tambudzai’s later conscientisation — like that of many Black children today who attend private schools — is a reaction to her exposure to blatant racism and sexism.

Although Tambu is the chief protagonist and narrator, she is not our heroine until perhaps the end. That role is her cousin Nyasha’s, the hyper-conscientised, incredibly sensitive daughter of a mission headmaster and teacher, who underwent profound culture shock during her parent’s studies in England and returned to Zimbabwe somewhat isolated from her peers by this experience. With lived experiences that come up lacking and the critical intelligence and boldness to question it, Nyasha dominates the book; Tambu, developing quietly, is her bard. Tambu calls Nyasha’s controversial thoughts and behaviour a “rebellion” but it is much more than this: it is a profoundly painful grappling with awareness of her oppression and her frustrated attempts to resist it.

Nervous Conditions struck me on two levels. One, it regales how children and young adults’ mental health is broken by systemic oppression. Two, it is a poignant reminder of the young age at which activists are conscientised. In a small room at the Apartheid Museum in Joburg hang 121 nooses, a representation of the 121 political executions under Apartheid. I was struck by how young they were, in their early twenties, as I am. It’s humbling, and perhaps inspirational, but also profoundly saddening.

According to Tambudzai, this book from Zimbabwe is the story of the four women she loved and the men in their lives. The conflict between the sexes (which is based on deep patriarchal beliefs) drives much of the book. The problem is always masculine, my French teacher used to say to help us remember the gender of that noun. That phrase rang in my head first as frivolous, self-important Nhamo stole his sister’s produce (as a child, Tambu cultivates and sells vegetables to pay for her school fees); then, as father Jeremiah slacked off and took credit for successes he in fact sabotaged (including Tambu’s plan to raise her school fees); as cousin Takesure followed in Jeremiah’s path and blamed his lover Lucia for his failure to abide by the family head’s orders; and finally as Babamukuru, the upright patriarch, raged against his daughter Nyasha, even coming to beating her, and seized his wife’s salary to maintain his role as head of the family.

And then there is the racism. It’s much subtler than the sexism and not at all physically violent in the book. Racism manifests primarily in the idealisation of westernisation and the degradation of local culture and systems. Nyasha is tortured by the racial oppression she sees and the impact it has on her father. Racism seems to drive the entrenchment of patriarchal traditions. Babamukuru seems to feel he carries the weight of representing all Black people; his daughter, then, must be faultness in her obedience, something her feminist convictions don’t allow. Jeremiah seems to exist in a threatened state: insecure by his lack of education, he relies on his brother’s Black tax to maintain the family as he struggles to successfully cultivate land the family was removed to. He seems to suffer from emasculation: he does not fulfil his role on the homestead, is threatened by his wife, children and brother’s successes, and seeks to reassert his authority by forcing the rest of the family into supporting him.

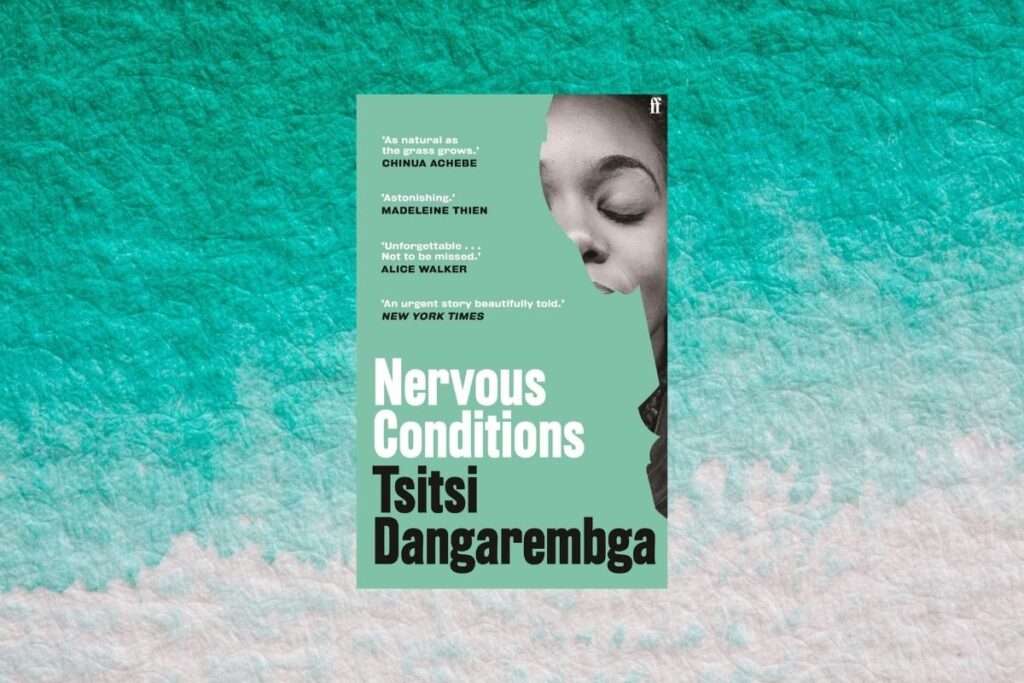

About Zimbabwean Author Tsitsi Dangarembga

It’s a testament to its brilliance that Nervous Conditions, a debut novel, has been acclaimed as one of “100 Stories that Shaped the World“. Author Tsitsi Dangarembga is a giant of Zimbabwean literature: the first Black Zimbabwean woman to have published a novel in English. She’s also an activist who made headlines in 2020 when she was arrested for her participation in anti-corruption protests in Harare.

In an interview with Aljazeera, Dangarembga explained why the personal lives of her characters are so political: “the whole greatness of human experience is really curtailed because of the political microcosm.”

If Zimbabwe had been like Germany, for example, you could have had so many different stories that do not really have to do with the politics of the day because your life is not individually every day determined by repression and poverty. That is the tragedy of Zimbabwean life: that life, the whole greatness of human experience, is really curtailed because of the political microcosm.

Tsitsi Dangarembga in an interview with Aljazeera.

She’s right. According to Safer Spaces, a community safety and violence prevention platform, structural violence goes beyond physical violence to “constrain/restrict an individual or a specific group of people.” This restriction is something that resonates across our own country.

What I Learned about Zimbabwe from this Book

Nervous Conditions is the first of a trilogy which tracks both Tambudzai and Zimbabwe’s growth. The country introduced in this first novel is not easily identified but the book is rich in specificity in a different way. The sense of broader identity in Nervous Conditions derives not from a national identity but a cultural identity. The integration of Tshona and traditional greetings reflects the family’s indigenous roots. Through Tambudzai we learn of the family’s origins as told to her by her grandmother and of the pivotal role traditionally played by women in agriculture.

There is also the meeting of Christianity and the indigenous belief system. When the family convenes to find a solution to Jeremiah’s poor productivity, he suggests a cleansing ceremony. His brother, horrified at the idea, posits that Jeremiah must marry the mother of his children. For Tambudzai, her parents’ marriage is a deeply insulting joke, seemingly because it undermines her legitimacy. On a deeper level, she is protesting the mockery it makes of the customary marriage the reader assumes they had, and therefore of their indigenous culture.

Is this the Zimbabwean Book for You?

Nervous Conditions is a classic of Zimbabwean literature and in that sense, it’s ideal for anyone looking to understand more about the country or Reading Africa like I am. With five strong women driving the story, it will be especially appealing to African feminists. Private school-educated Black youth will also be able to relate to Tambudzai’s experience of difference at the convent school. Based on this, it’s definitely one of the best books from Zimbabwe to get reading about our neighbours to the north.